A Tasmanian Affair Part 3

- Paul McGillick

- Mar 1, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2024

I was just kidding…Antarctica has no cultural significance for Tasmania apart from the fact that Hobart is the base for Australia’s Antarctic research.

But the Arctic, maybe, because Sir John Franklin, who was Lieutenant-Governor in Tasmania from 1836 to 1843, came to the colony as an already famous explorer of the Canadian Arctic. And he subsequently died there in 1847.

Certainly, Franklin and his wife, Lady Jane, were of huge cultural significance – Tasmania’s equivalent of the Macquaries in Sydney (1809-22). Franklin inherited a prosperous jurisdiction, but one seething with tensions between the aspirations of the free settlers (who had begun to arrive from 1816) and the island’s role as a penal colony. Those tensions saw off Franklin’s predecessor, George Arthur, and ultimately Franklin himself who was recalled against his wishes in 1843.

The Franklins’ ambition was to civilise this fractious colonial outpost. Accordingly, they championed science, natural history, the arts and education.

Clarendon Mansion (National Trust)

But it was not entirely uncivilised before the Franklins arrived. The aspirational free settlers – notwithstanding the war of attrition with the Aboriginals – were often idealists (‘radicals’, according to Franklin’s Private Secretary, Alexander Maconochie) seeking a more enlightened society than the one they had left. An example of their aspirations was their enthusiasm for cultivated gardens.

A view of the artist’s house and garden, John Glover (NGA)

The visual arts were also cultivated. Just as it was back home in Britain, skill in watercolour painting was esteemed as a key social grace, while prosperous farmers sought to advertise their success through grand, neo-Classical villas such as Panshanger Houseat Longford (1825-35),Longford House(1834), Clarendon Mansion(1838) and Woolmers Estate (1843), all of which still stand today.

Because of its extraordinary natural beauty and the sense that it combined a sense of home with the exotic (it was a favourite holiday destination for employees of the British East India Company), Van Diemen’s Land attracted a stream of artists, either as permanent residents or for extended stays.

The Bath of Diana, John Glover (NGA)

John Glover, who arrived in 1831, proved to be a major influence, not just as an artist, but also as an advocate for a more refined sensibility through painting. As a painter, Glover combined symbolism, indeed idealism, with an eye for accurately depicting the colours of the Tasmanian landscape, the unique character of the trees and the special qualities of the light. For Glover, Tasmania was a new Garden of Eden both for the colonial settlers, and for the Aborigines – before their way of life was fatally disrupted by fast-spreading European settlement.

Glover had been preceded by Thomas Bock (arr. 1823), George Francis Evans (1826) and W.B. Gould (1827). Later arrivals were Benjamin Duttereau (1832) who gave the first art lecture in Tasmania in 1833, Robert Dowling (1834), James Fenton (1834), Thomas Napier (1834), Thomas Griffiths Wainewright (1837), F.G. Simpkinson de Wesselow (1844) and Henry Mundy (1848), while Joseph Lycett (1819-21), Augustus Earle (1825) and John Skinner Prout (1845) made extended visits and had a significant impact on the artistic life of the colony.

Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens

Hobart’s Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens were established in 1818, just two years after Sydney’s. Today, in my view, they surpass the Sydney gardens for the way in which they combine intimacy with dramatic prospect.

The first Mechanics’ Institution in Australia was established in Hobart in 1826 and, although it did not teach art as such, was a major ‘civilising’ influence. The first amateur painting group was set up in 1831 and the first art exhibition in Australia was held in Hobart in 1837.

But it was the Franklins, in their relatively short interregnum, who really pushed for a cultural maturity which, for a time, made Tasmania the ‘cultural capital’ of Australia.

In education, Sir John established a system of secular primary and secondary schools along with a scholarship programme for Tasmanians to attend British universities. He and Lady Franklin supported artists such as Thomas Bock and John Gould during his stay painting the birds of Tasmania, along with a general encouragement of the arts. They established the Tasmanian Natural History Society in 1838 which subsequently evolved into the first branch of the Royal Society outside of Britain.

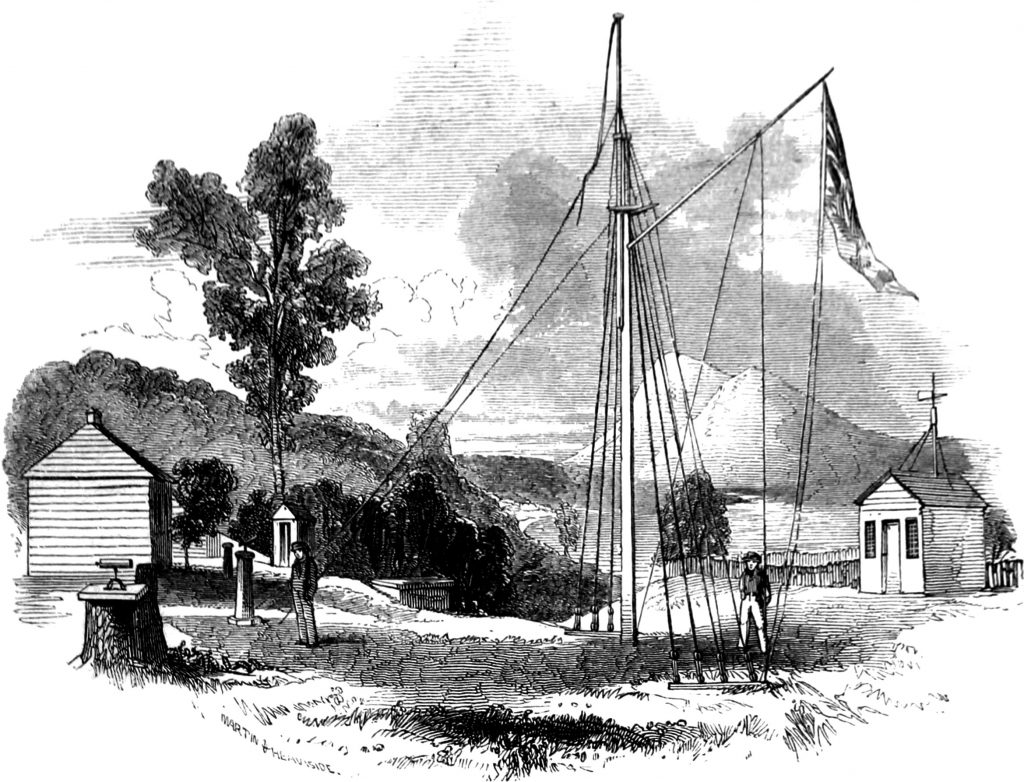

Rossbank Observatory – Hobart Town, J. E. Davis

The Franklins also facilitated the building of the Rossbank Observatory in 1840 in collaboration with polar explorer, James Clarke Ross, as part of a worldwide chain of magnetic observatories.

And what about that first museum?

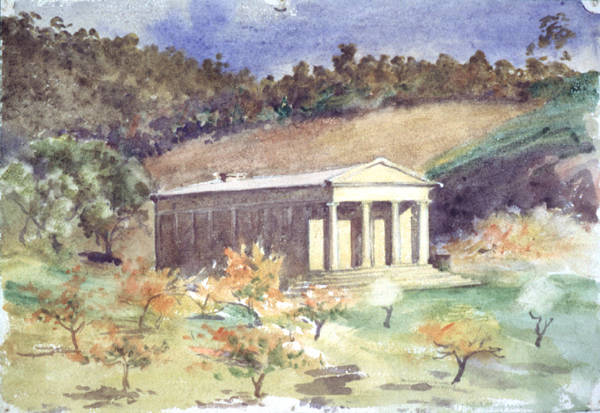

Well, the Australian Museum was established in Sydney in 1827, but did not have its own dedicated building open to the public until 1857. However, Lady Franklin facilitated the establishment of a museum of the arts and natural sciences on a grant of 400 acres in the foothills of Hobart’s Mount Wellington in 1842. So, Tasmania can claim to have built the first museum in Australia. Sadly, it fell into neglect following the Franklins’ departure, but was ultimately saved from terminal decay and restored. This modest, charming neo-Classical building, initially named Acanthe (‘blooming valley’), but now called Lady Franklin’s Museum, still stands today and is home to the Tasmanian Art Society.

Acanthe, Curzona Allport (undated)

And if the apple isle wants further bragging rights – the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery was established in Hobart in 1846, initially housed in Customs House (later home to Parliament), then from 1862 in its own dedicated building known at that time as the Royal Society’s Museum and designed by Henry Hunter. It brought together a number of existing collections, including those of the Royal Society and the Mechanics’ Institution, and later that of Lady Franklin’s Museum.

The Art Gallery of NSW, on the other hand, was opened only in 1874, moving to its Walter Liberty Vernon-designed permanent home in 1897. The National Gallery of Victoria evolved over time, starting in the Public Library in 1861 and only really achieving physical independence with the opening of the Roy Grounds- designed building on St Kilda Road in 1968.

Like all island states, Tasmania has a tendency to paddle its own canoe – which is what whets my appetite for the remarkable cultural history of the place. This cultural uniqueness continues to this day, generally overlooked by ‘mainlanders’, even by Tasmanians themselves. But it is manifest across the board – painting, printmaking, music, artisanal design, product design, architecture and boat building, not to mention being a pioneer in conservation.